This is the one skill your child needs for the jobs of the future

Where can your kids learn creativity and critical thinking? The answer is simpler than you think

Fuente: www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/09/skills-children-need-work-future-play-lego/?utm_content=buffer75105&utm_medium=social&utm_source=facebook.com&utm_campaign=buffer

However, this mindset is often eroded or even erased by conventional educational practices when young children enter school.

The Torrance Test of Creative Thinking is often cited as an example of how children’s divergent thinking diminishes over time. 98% of children in kindergarten are “creative geniuses” – they can think of endless opportunities of how to use a paper clip.

This ability is reduced drastically as children go through the formal schooling system and by age 25, only 3% remain creative geniuses.

Most of us only come up with one or a handful of uses for a paperclip.

What is most concerning in connection with the human capital question is that over the last 25 years, the Torrance Test has shown a decrease in originality among young children (kindergarten to grade 3).

By the way, did you know you could combine six standard LEGO bricks in more than 915 million ways?

Wrong focus

The World Economic Forum has just released its Human Capital Report with the subtitle “Preparing People for the Future of Work”.

The report states that «many of today’s education systems are already disconnected from the skills needed to function in today’s labour markets».

It goes on to underline how schools tend to focus primarily on developing children’s cognitive skills – or skills within more traditional subjects – rather than fostering skills like problem solving, creativity or collaboration.

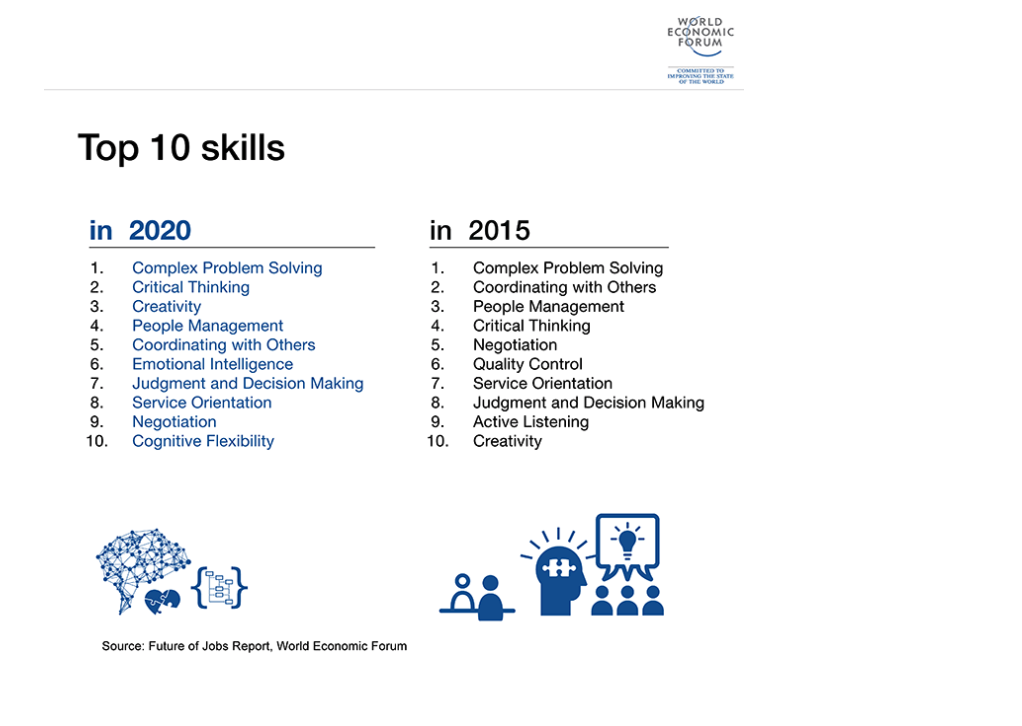

This should be cause for concern when looking at the skill set required in the Fourth Industrial Revolution: Complex problem solving, critical thinking and creativity are the three most important skills a child needs to thrive, according to the Future of Jobs Report.

Let’s take a moment to underscore that creativity has jumped from 10th place to third place in just five years.

And that emotional intelligence and cognitive flexibility have also entered the skills list for 2020.

Worryingly, these skills are often not featured prominently in children’s school day where the norm still is the chalk-and-talk teaching approach that has prevailed for centuries.

Child’s play

A study in New Zealand compared children who learned how to read at age five with those who learned at age seven.

When they were 11 years old, both sets of children displayed the same reading ability. But the children who only learned how to read at age seven actually showed a higher comprehension level.

One of the explanations is that they had more time to explore the world around them through play.

It is clear that preparing children for the future demands re-focusing concepts of learning and education.

Knowing how to read, write and do maths remain important for children to unlock the world in front of them.

An increasingly interconnected and dynamic world means children will find themselves changing jobs several times during their lives – switching to jobs that don’t exist today, and which they might have to invent themselves.

The question is how do we foster the above-mentioned breadth of skills, and keep alive the natural ability of children to learn throughout a lifetime – instead of eroding it when they enter formal schooling?

Achieving this is simpler than you might think: engaging children in positive, playful experiences.

Different forms of play provide children with the opportunity to develop social, emotional, physical and creative skills in addition to cognitive ones.

Lifelong play

If we agree on the urgent need for developing skills of complex problem solving, critical thinking and creativity, it is essential that we recognise that these skills are built by learning through play across the lifespan.

As we invest in our children’s future, let’s be sure to guard against directed learning, “schoolification” or three-year-olds learning their alphabet and numbers in written form when there is no evidence that this will make them better readers.

We need to challenge ourselves on the logic of flashcards and homework for our youngest at home, and see the value of continuing to create joyful, meaningful play moments with our children.

The natural ability of children to learn through play may be the best-kept, low-cost secret for addressing the skills agenda with potential to equip both our children and our economies to thrive.

Plus, it’s fun. So, what’s stopping us? Let’s play!