Traducción Lucio Henao desde Fuente https://bit.ly/3hi8uQp – Diciembre 26 2020

RESUMEN

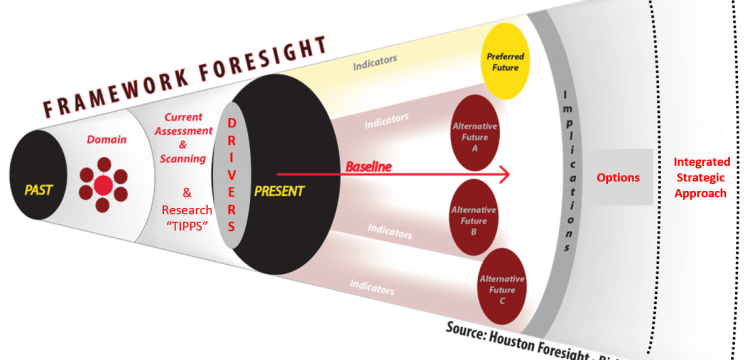

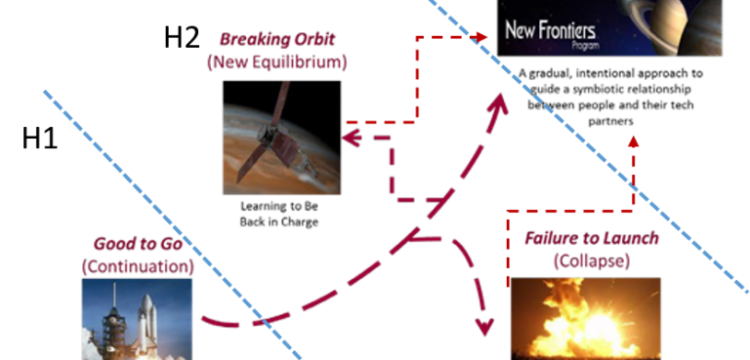

La gestión de la pandemia de COVID-19 es un nuevo desafío global que se aborda en tiempo real. Si bien algunos países y regiones del mundo han tenido una experiencia más reciente en el manejo de virus similares (como el SARS), todos han tenido que lidiar con el nuevo virus corona y los nuevos desafíos que presenta. Las respuestas de las políticas públicas cambian rápidamente, a veces a diario. Este artículo se centra en cómo las narrativas de prospectiva han impactado la formulación de políticas en relación con la pandemia de COVID-19. Más específicamente, proporciona una descripción general del uso de la previsión en el sector público antes de la pandemia. También investiga las narrativas clave en circulación durante la implementación de los objetivos estratégicos de los gobiernos y la realización de visiones de una sociedad ‘libre de pandemias’. El enfoque utilizado aquí es el de la previsión narrativa que se centra predominantemente en las historias que los individuos, organizaciones, estados y civilizaciones se cuentan sobre el futuro. Además de las narrativas generales, el artículo también investiga más específicamente las metáforas más utilizadas antes y durante la pandemia de COVID-19. El objetivo del artículo es determinar qué lecciones podemos aprender en términos de éxitos y fracasos de la narrativa ‘previsión en acción’, para poder utilizar este conocimiento para futuros problemas globales. Finalmente, el artículo sostiene que muchas metáforas y narrativas actuales están vinculadas a «falacias del futuro», patrones de pensamiento perjudiciales sobre el futuro.

COVID-19: ¿fuimos advertidos?

“’No’, dije, ‘no ha pasado nada nuevo. Las plagas son tan seguras como la muerte y los impuestos ‘”([Krause 1982] citado en Krause, 1993: xviii).

El papel de la retrospectiva es destacado si deseamos mejorar la previsión. El papel de los eventos históricos, las percepciones y las advertencias es fundamental para cualquier trabajo de prospectiva informado. Es decir, necesitamos saber lo que podemos aprender de la historia y necesitamos saber cómo podemos mejorar nuestro pensamiento sobre el futuro tanto ahora como en el futuro.

Investigaciones anteriores sobre los procesos de prospectiva del sector público indican claramente lagunas en el conocimiento (por ejemplo, Calof y Smith, 2012; Cameron et al., 2006; Coates, 2010; Conway y Stewart, 2004; Cook, et al., 2014; Cuhls y Georghiou, 2004 ; Da Costa et al., 2008; Dator, 2007, 2011; Dreyer y Stang, 2013; Greenblott et al, 2018; Havas et al., 2010; Jennings, 2017; Kuosa, 2012; Savio y Nikolopoulos, 2009; Schartinger, et al., 2012; Solem, 2011; PNUD, 2014). También se ha identificado previamente una “dramática falta de pensamiento y planificación avanzados” específicamente relacionada con las pandemias (Rubin, 2011: 63). Además, las “lecciones aprendidas” de brotes anteriores de enfermedades infecciosas y las “recomendaciones para el futuro” de la preparación para una pandemia se recogieron en varias publicaciones durante las dos últimas décadas (por ejemplo, Brundtland, 2003; OMS, 2009; Rubin, 2011; Morse et al, 2012; OMS, 2015; Ross et al, 2015; ONU, 2016; OMS, 2017; OMS, 2018; GPMB, 2019). Este artículo tiene la intención de vincular los hallazgos anteriores en el contexto de la ‘previsión en acción’ (Van Asselt. Et al., 2010): si se utilizó este conocimiento y cómo.

El primer punto que hago aquí es que, contrariamente a las opiniones sostenidas por algunos, la previsión relacionada con la próxima pandemia NO fue “trágicamente escasa” (Davies, 2020). Ciertamente, las historias que cuentan los diferentes actores sobre el pasado, el presente y el futuro son muy diferentes y, de hecho, las narraciones de “ nadie sabía ”, “¿ quién lo hubiera pensado? ”,“ Nunca antes ”y el“ shock pandémico ”han sido abundantes. Sin embargo, también lo han hecho las narrativas de » es sólo una cuestión de tiempo «, » tenemos que empezar a prepararnos ahora » y «el tiempo se acaba”. Este último conjunto de narrativas está presente en numerosos documentos publicados por diversos organismos mundiales y nacionales, así como en trabajos de investigación académica y libros que anticipan la posibilidad de una pandemia. La mayoría repite el ‘mantra’ de la preocupación por: (1) la pandemia inminente y (2) la falta de preparación en todos los niveles de gobierno. Antes de abordar el tema de la falta de preparación para la pandemia actual, primero proporciono ejemplos de la aplicación de la previsión, anticipando riesgos y desafíos, en el sector público.

COVID-19: ¿predicho y prevenido pero no prevenido?

When COVID-19 was first identified in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, there were already many documents published by various global and national bodies as well as academic research papers and books that anticipated the possibility of a pandemic. Some ‘highlights’ include the following:

“And for the next outbreak, of SARS, or, perhaps a new, more infectious and more deadly illness. We may have very little time. Let us use it wisely.” (Brundtland, 2003)

“Future pandemic threats will emerge and have potentially devastating consequences.” (UN, 2016: 8)

“…despite … the looming threat of a pandemic … [n]ational health security is fundamentally weak around the world. No country is fully prepared for epidemics or pandemics, and every country has important gaps to address.” (Cameron et al., 2019: 6,9)

In addition to the citations above, similar warnings were part of various publications emphasising the narrative of the forthcoming pandemic and lack of preparedness.

For example, a discussion about “a major pandemic outbreak” including efforts to “upgrade our global preparedness to identify and isolate new diseases” features in the World Economic Forum’s 2007 Global Risk Report. It then reappears in 2008, as follows:

“A pandemic disease jumps from the animal population to humans, with high mortality and transmission rates.” (WEF, 2008: 22)

[And since] “global travel patterns have made the risk of a pandemic homogenous across the world [a]ll countries are equally vulnerable to a pandemic that originates in one country”. (WEF, 2008: 29)

An academic publication from the same year (Jones et al, 2008: 990) similarly argued that:

“Emerging infectious diseases (EIDs) … have risen significantly over time … the majority of these (71.8%) originate in wildlife … EID origins are significantly correlated with socio-economic, environmental and ecological factors, and provide a basis for identifying regions where new EIDs are most likely to originate (emerging disease ‘hotspots’).”

Many decades prior, Richard Krause, the author of The Restless Tide: The persistent Challenge of the Microbial World (1981) warned that “…emerging viruses know no country. There are no barriers to prevent their migration across international boundaries or around the 24 time zones.” (Krause, 1993: xvii)

In 2009, the World Health Organisation (WHO) issued a Whole of Society Pandemic Readiness document wherein they asked the question of “Why do pandemic planning beyond health care?” and to which they responded in the following manner:

“Given that a pandemic of any severity will have consequences for the whole of society, it is essential that all organizations, both private and public, plan for the potential disruption that a pandemic will cause … While many countries have made substantial efforts to prepare for the health consequences of pandemics, not all countries have yet given sufficient attention to preparing for the economic, humanitarian and societal consequences.” (WHO, 2009: 5)

Warnings about the economic fallout that could arise if we were to experience a pandemic were given as well. For example:

“…the world [is]highly vulnerable to massive loss of life and economic shocks from natural of human-made epidemics and pandemics. … The inclusive costs of the next … pandemic could be US$570 billion each year or 0.7% of global income … Given the magnitude of the threat, we call for scaled-up financing of international collective action for epidemic and pandemic preparedness.” (WHO, 2017: 742)

A few years prior, the President of the World Bank called for the creation of a new pandemic emergency facility:

“planning must … begin for the next pandemic, which could spread much more quickly, kill even more people [than Ebola]and potentially devastate the global economy” (The World Bank, 2014)

Concerns were also raised about “the increasing frequency of pandemics occurring over the last few decades.” (Ross et al, 2015: 89) Specifically, and “worryingly” (Ross et al, 2015: 89):

“…the frequency between pandemics seems to be disturbingly shorter as evident with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in 2003, Influenza A H1N5 (bird flu) in 2007, H1N1 (swine flu) in 2009, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in 2012 and Ebola in 2014. … Clearly, the window of opportunity to act is closing.”

Given this context, the UN Secretary-General established the High-level Panel on the Global Response to Health Crises in April 2015 (UN, 2016). The Panel also noted that:

“…the high risk of major health crises is widely underestimated, and that the world’s preparedness and capacity to respond is woefully insufficient. Future epidemics could far exceed the scale and devastation [of previous outbreaks]. [Their emergence] could rapidly result in millions of deaths and cause major social, economic and political disruption.” (UN, 2016: 5)

Over time, the warnings became more alarmist. In May 2018 the World Bank and the WHO co-convened the Global Preparedness Monitoring Board which in their first annual report on global preparedness for health emergencies stated the following:

“…there is a very real threat of a rapidly moving, highly lethal pandemic of a respiratory pathogen killing 50 to 80 million people and wiping out nearly 5% of the world’s economy. A global pandemic on that scale would be catastrophic, creating widespread havoc, instability and insecurity. The world is not prepared.” (GPMB, 2019: 6)

Examples of pandemic awareness and foresight among national and regional governments

Parallel to global bodies or globally-oriented analysis, various national governments and academics analysing specific countries’ or regions’ pandemic preparedness were also aware (and gave warnings) of the emerging threat of infectious diseases (EID). Here are some US-based examples:

“…a growing concern by senior US leaders … the growing global infectious disease threat. … New and reemerging infectious diseases will pose a rising global health threat and will complicate US and global security over the next 20 years.” (NIC, 2000: 1, 5)

“If we wait for a pandemic to appear it will be too late to prepare. And one day many lives could be needlessly lost because we failed to act today.” (George Bush 2005, cited in Mosk, 2020)

In the UK, a series of 2006 publications were part of the foresight project entitled Infections Diseases: Preparing for the future which looked 10-25 years ahead in order to “consider infectious diseases in humans, animals and plants” (Brownlie, et al, 2006: 64). Whilst recognising that “predicting our disease future with precision is not possible” (ibid.:63), nonetheless, amongst the “eight global disease threats” the authors identified “new pathogens or novel variants of existing pathogens” and “zoonoses” (ibid.: 23). They also wrote the following:

“Nearly 40 ‘new’ human pathogens were first reported in the last 25 years, and the majority of these had zoonotic origins. The risk of zoonotic infection shows no sign of diminishing and may well increase in the future … diseases that cross species [are]… one of the top future risks.” (Brownlie et al, 2006: 32)

Moreover, in the section investigating “China – future trends in human and animal infectious diseases” the authors recognised “the importance of Asia as a source of zoonotic diseases, and China as an important country in the region” (Brownlie et al, 2006:64). Finally, future gaps and trends in vulnerabilities in China for human and animal infectious diseases were also identified, such as:

“Illegal practices … Lack of interaction between policy and regulatory agencies leading to delays in detection and identification … [and]Problems across international agencies, particularly barriers to the sharing of data.” (Brownlie et al, 2006: 68)

Such very specific warnings are also present in academic papers, for example:

“The presence of a large reservoir of SARS-CoV-like viruses in horseshoe bats, together with the culture of eating exotic mammals in southern China, is a timebomb. The possibility of the reemergence of SARS and other novel viruses from animals or laboratories and therefore the need for preparedness should not be ignored.” (Cheng et al. 2007: 694)

Similar narratives are replicated elsewhere. For example, a thorough 2008 analysis of national preparedness plans in the African region concluded the following (Ortu et al, 2008: 161-169):

“With 35 countries of 53 having drafted and approved plans since November 2005, preparation efforts for an influenza pandemic in the African region have advanced considerably. … Africa faces many challenges and the limited surveillance capacity to pandemic …the human health care sector is ill-prepared.”

More recent (Kinsman et al, 2018: 2) analysis of “Preparedness and Response Against Diseases with Epidemic Potential in the European Union” ascertained that:

“Infectious disease outbreaks remain as an ongoing threat. Efforts are required to ensure that core public health capacities for the full range of preparedness and response activities are sustained.”

The same year, the World Bank analysed pandemic preparedness in East Asia and the Pacific and highlighted the following:

“Countries in East Asia and the Pacific made tremendous efforts to tackle emerging infectious diseases; however, many challenges remain to ensure that resilient health systems and pandemic preparedness are sustainably financed.” (The World Bank, 2018)

The MENA region as well, had previously:

“… missed out on opportunities to advance patient research during prior infectious disease outbreaks caused by the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, Ebola, and the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, as evidenced by the lack of concerted research and clinical trials from the region.” (Ibrahim et al, 2020: 106106)

These examples are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the use of foresight prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. In summary, the current pandemic was widely anticipated and many warnings in terms of actions needed to ameliorate human suffering and economic cost were given. There is also a consensus that even the most alarming warnings did not adequately translate into the level of preparedness in the public sector which such a future pandemic would require. The next section of this article aims at suggesting that in addition to the usual ‘suspects’ – e.g. a lack of political will, coordination or funding – detrimental thinking patterns about the future, termed futures fallacies, (AUTHOR, 2020a) were also salient.

COVID-19 futures fallacies

Futures fallacies are a broader issue which I’ve investigated in three previous publications (AUTHOR, 2020a, 2020b and 2020c). In the following sections of this article, I further explore the futures fallacies as they relate specifically to lack of adequate preparedness for COVID-19. The purpose of this investigation is to: (1) map some of the reasons behind the lack of pandemic preparedness related to how we often think about the future, and (2) enhance narrative foresight within the public sector at the global, national and local level. The narratives under investigation have been circulating in both public policy documents (inclusive of academic publications) and public discourse (inclusive of political discourse) – in relation to epidemics/pandemics in general and COVID-19 in particular.

It is very clear from this investigation that a number of cognitive and futures fallacies converged so as to prevent an adequate pandemic preparedness response. They ensured that the strategies needed to manifest desired longer-term futures were missing or insufficiently applied (AUTHOR, 2020a, 2020c). They also ensured that the best existing evidence, facts, and logic, of relevance to emerging futures, fell on deaf ears (AUTHOR, 2020a, 2020c).

Denial: just a flu

To start with, one of the longest and best documented cognitive fallacies – denial – has been abundantly present in narratives both before and during the pandemic. One example of this fallacy is the narrative of COVID-19 being ’just a flu’. What is problematic in this narrative is perhaps not so much comparison with the flu, but morethe adverb ’just’. The yearly global toll from ’just the flu’, as estimated by WHO (2019), is 1 billion cases, of which three to five million are severe cases, “resulting in 290 000 to 650 000 influenza-related respiratory deaths“. Unfortunately, foresight itself may have contributed to this narrative. Since the early 1990s, many epidemiologists and governments anticipated that a new pandemic might be related to influenza (e.g. Webster, 1997; WHO, 1999; NIC, 2000; HSC, 2005; AHMPPI, 2014; Ross et al, 2015). Even though those reports warned of ‘other’ possible infectious diseases, and also new emerging influenza viruses to which there is no immunity, timely vaccine or adequate treatment, the ‘just the flu’ narrative seemed to have stuck. And perhaps “[framing a new EID as a flu]was a mistake; telling people the next pandemic would be caused by influenza didn’t make it seem nightmarish at all. The flu? I get that every year. We have a vaccine for that.” (Henig, 2020)

Foresight based documents also repeatedly warned that no pandemic can be accurately predicted. Still, the warnings were often about the details of the prediction rather than whether prediction discourse is in itself problematic. For example:

“With such a small number of cases, it is impossible to predict future numbers of cases of the human disease…” (Murphy, 1998:433, underline mine)

“Although the timing cannot be predicted …” (HSC, 2005:1, underline mine)

“While the source and virulence of the next emerging pathogen are difficult to predict…” (UN, 2016:29, underline mine)

“African experts concurred with the prediction that HIV/AIDS, malaria and respiratory infections including tuberculosis will remain the most important infectious diseases in Africa in coming decades.” (Brownlie et al, 2006:35)

Prediction: the boy who cried wolf

Once again, the problem here is not in trying to identify early warning signals and emerging issues, but the futures fallacy of prediction (AUTHOR, 2020a, 2020c). The main danger with this fallacy is that genuinely valid warnings about the future are not heard due to previously ‘failed predictions’, even though, given the sheer volume of predictions made on a daily basis, it is always possible to find predictions which have, in retrospect, been shown to be true. The metaphor of ‘the boy who cried wolf’ perhaps best summarises this futures fallacy in the context of COVID-19. Krause (1993: xviii) for example, describes efforts to forestall a 1975 epidemic amongst a small number of soldiers at Fort Dix, NJ, USA. In order to prevent a possible repetition of the 1918 flu pandemic, “within 9 months a specially formulated vaccine was mass produced and millions of Americans were immunized” Krause in Morse, 1993: xviii). However, for whatever reason, that particular flu did not go global. In fact, except for AIDS, the same was the case with many other emerging infectious diseases (EIDs), e.g. SARS in 2003 (mostly stayed in Asia), MERS in 2012 (mostly stayed in the Middle East) and Ebola in 2014 (mostly remained in west Africa). Which may explain why – having seen so many “This Is the Big One” threats flaming out, we ended up “inured to the real threat of a true international crisis” (Henig, 2020) prior to and at the beginning of COVID-19 pandemic.

Given how long ‘the most likely to endanger us’ lists have been getting, it’s not surprising many became overwhelmed or simply gave up. The public sector in most countries is stretched and struggling to meet competing and changing demands. So on one hand, in our globalised and interconnected world, humanity is better equipped to manage pandemic risks. On the other hand, the exponential rate of social change and the cultural, demographic, environmental, technological and economic challenges of our time make such tasks increasingly difficult. COVID-19 response has been termed “the greatest global science policy failure in a generation” (Horton, 2020a). And yet, when governments did act successfully in the past, for example, during the outbreak of the 2009 swine flu pandemic, many were subsequently critiqued for their ‘over-reactiveness’ as well as high spending on the vaccine and other medical supplies. In 2010 the German magazine Spiegel, for example, asked the question of how and why the world overreacted, using terms such as ‘the swine flu panic’ and ‘reconstruction of a mass hysteria’. ‘Damned if you do, and damned if you do not’ may be a metaphor best summarising public sector dilemma in face of the type and intensity of a response to be chosen.

Overinflated agency: ‘othering’ the virus

The futures fallacy of overinflated agency which commonly relegates and reaffirms responsibility (AUTHOR, 2020a, 2020b, 2020c) – in this case to the public sector and government leaders – only adds fuel to the fire. The fallacy of overinflated agency is also behind conspiratory thinking which proportions blame to an individual, organisation or group of people – e.g. Bill Gates, George Soros or Huawei and 5G networks, as heard during the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, ‘mysterious’ and ‘unconquered’ diseases, in particular, tend to unleash a “tsunami of hate and xenophobia, scapegoating and scaremongering.” (Guterres cited in Davidson, 2020) The ascent of HIV-AIDS in the 1980s, for example, engendered fear and hatred against social groups seen as combatants in the “AIDS invasion of North America.” (Gilman, 1987: 87) Those were the “five ‘H’s – homosexuals, heroin addicts, Haitians, haemophiliacs and hookers.” (Cohn, 2015: 538). The current “China-virus” or “kung-flu” metaphors similarly aim to apportion blame. What is behind it is yet another powerful metaphor of “nation-as-organism”, where “just as the body may be threatened by contaminating foreign elements, the social body is treated as vulnerable to corruption by invading sub-groups.” (Bin Larif, 2015: 97) This group of people could include anybody deemed as ‘the other’, from foreign nationals, migrants and refugees, to recently returned travellers (UN 2020).

Overinflated agency and prediction: warnings versus predictions

Returning to the futures fallacy of prediction, this fallacy makes anticipation in general and distinguishing between the ‘signal and the noise’ (Silver, 2012) in particular even more precarious. For example, “between 1940 and 2004 there were 335 emerging infections diseases (EID) origins reported globally” (Ross et al, 2015: 90). It is “estimated that there are 354 generic infectious diseases in the world today [2017]” (BFI, 2017). Since 1980, “a new infectious disease has emerged in humans at an average of one every four months.” (UNEP, 2016: 65). In the period between 2009 and 2019, the (now defunct) PREDICT program has “identified 1,200 different viruses that had the potential to erupt into pandemics, including more than 160 novel coronaviruses” (Baumgaertner and Rainey, 2020). Over 90 infectious disease outbreaks were identified by WHO in 2018 and nearly 120 in 2019 (WHO, 2020a). In the year 2020 “pneumonia of unknown cause – China” (5 January) and “novel coronavirus – China” (23 January) make an appearance. But so do Ebola, MERS-CoV, Measles, Lassa fever, Yellow fever, Dengue fever, Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease), Influenza A(H1Ns), Plague, Chikungunya and Monkeypox – all in multiple parts of the world. Most of those diseases were, once again, contained to particular regions. But so was ‘novel coronavirus-China’ on 11 and 12 January 2020 (WHO, 2020b):

“The evidence is highly suggestive that the outbreak is associated with exposures in one seafood market in Wuhan. … Among the 41 confirmed cases, there has been one death. … Currently, no case with infection of this novel coronavirus has been reported elsewhere other than Wuhan.”

Fast forward to 1 October 2020 where 41 confirmed case in one Chinese city has grown to 33,842,281 confirmed cases and 1,010,634 deaths with cases present in 235 countries, areas or territories (WHO, 2020c). Volumes will be written about ‘what went wrong’ and how come this particular virus/case – amongst so many – spiralled ‘out of control’. Of course, all this will be done retrospectively.

The problem with the future fallacy of prediction is that it may exacerbate some government’s reluctance to get on board with important projects or politicians’ criticism of organisations doing ‘prediction’ for not getting it ‘exactly right’. Important recommendations may be seen as a ‘waste of time and money’, given that prevention rarely gives politicians ‘hero status’ or ‘helps them cut the ribbon’ (Inayatullah, 2018: 20). Spending time on getting ‘the right signal amongst the noise’ or deciding what should be on the top of ‘the most likely to endanger us’ lists is understandable. In the changing world, citizens and governments want some certainty which prediction discourse is more than happy to provide. At the same time, efforts there may mean that more important messages are ‘lost in the process of translation’. For example, the messages about: (1) the importance of early warning systems, (2) addressing underlying drivers for the diseases, (3) putting generic preventative measures in place, (4) developing futures literacy in general, (5) developing a foresight-oriented agile public sector in particular, and (6) acting early and decisively while also (7) being flexible in needed responses as circumstances change. In other words, the underlying assumption is that warning signals can safely be ignored until they become a full-blown problem. The difference between warnings which are about possibilities and predictions which are about certainties may be subtle. However, this difference is critically important and it is crucial that we find a way to communicate it more clearly in future foresight projects.

The arrival and the exemption: the west as an infection-free utopia

Three other futures fallacies go hand in hand with the futures fallacy of prediction: (1) linear projection, (2) ceteris paribus and (3) the arrival futures fallacies (Dorr, 2016). Taken together, they presume (Dorr, 2016): (1) that future change will be a simple and steady extension of past trends (such as extrapolation of past pandemics), (2) that it is sufficient to consider only one single aspect of change (such as the spread of the pathogen) and (3) that possible futures are envisioned as static objects like a destination or goal (such as arresting the epidemic’s spread, elimination of the virus/pathogen).

For example, the linear projection fallacy has been behind the long-standing belief that infectious diseases were ‘conquered’ and nature ‘controlled’ by science and technology. While prior to the twentieth century it was thought that infections were “part of the human condition” (Wilson, 1994), modern scientific and technological advances had “facilitated the control or prevention of many infectious diseases, particularly in industrialized nations.” (CISET 1994). Antibiotics and other drugs, vaccines against childhood diseases, and improved technology for sanitation (CISET 1994), made it appear that we had arrived, or were in the process of arriving, to ‘post-nature’ societies. This led both the public and many experts to expect nearly complete freedom from infectious diseases (Wilson, 1994).

Influenced by the linear projection, ceteris paribus and the arrival futures fallacies, the mainstream global discourse of the mid to late 20th century has thus been one where, at least partially, it is assumed that the western industrialized nations ‘have arrived’ to the stage of an ‘infection-free utopia’. It was also assumed that the rest of the world will follow, providing it adopts the same standards of hygiene, immunisation and medical care.

Future personal exemption: out of sight, out of mind

However, yet another futures fallacy – of future personal exemption – made industrialized nations blind to the facts of the old and new infectious diseases elsewhere. Numerous regulatory frameworks, including those by the International Health Regulations (IHR), World Health Organisation (WHO) and World Health Assembly (WHA), were critiqued on the basis that the regulations pose an enormous obligation for all but are “primarily developed to protect the health and welfare of developed nations” (Ross et al, 2015: 91). COVID-19 has laid bare errors in governance committed by the “global health leaders”, more than 80% of whom are nationals of high-income countries and half being nationals of the UK and the USA (Dalglish, 2020: 1189). Moreover, “85% of global organisations working in health have headquarters in Europe and North America; two-thirds are headquartered in Switzerland, the UK, and the USA.” (Dalglish, 2020:1189) And, consequently but short-sightedly, “the majority of the scientific and surveillance effort [is]focused on countries from where the next important EID is least likely to originate.” (Jones et al, 2008: 990)

This global power imbalance has had two important implications. First, ‘out of sight, out of mind’, including questions of what constitutes an epidemic worth looking into (Henig, 2020). And, second, the myopia blinding us globally to “the strengths of the COVID-19 [and other EID]response in Africa and Asia”, i.e. in some countries which have, despite limited resources, adopted measures perhaps “worth imitating.” (Dalglish, 2020: 1189)

Dynamics similar to those which takes place globally can be observed within a single country as well. For example, the UK’s government advisers are “narrowly drawn as scientists from a few institutions … [consequently they]took narrow a view and hewed to limited assumptions (Grey and MacAskill, 2020). Policy makers all around the world tend to have similar backgrounds (educated, middle- or upper-class background, dominant ethnic or religious group) – they “often unintentionally frame policy problems from a narrow world view, and often it is their own.” (Terranova, 2015:372) Expertise that exists in a number of marginalised spaces – e.g. local, indigenous knowledge – may thus be neglected. But it is precisely this type of knowledge and expertise – from various globally marginalised places – that has to be included if the fallacy of future personal exemption is to be addressed.

To strengthen this latest point, it is perhaps worth mentioning that in the 2019 Global Health Security Index, an assessment of 195 countries’ capacity to face infectious disease outbreaks – compiled largely by US-based experts – it is the USA which is ranked first in terms of overall preparedness score, followed by the UK, Netherlands, Australia and Canada (Cameron et al., 2019). In light of the devastating COVID-19 death rate and other policy failures in the US, the authors of the GHSI have since provided a further elaboration as to the “significant preparedness gaps” in the US (GHSI, 2020):

“The United States’ response to the COVID-19 outbreak to date shows that capacity alone is insufficient if that capacity isn’t fully leveraged. Strong health systems must be in place to serve all populations, and effective political leadership that instils confidence in the government’s response is crucial.”

It is beyond doubt that ‘leveraging capacity’, having a ‘strong public health system’ and ‘effective political leadership’ are all critical for any future pandemic preparedness and adequate response. But so is addressing the fallacy of future personal exemption which makes it less likely for wealthy and powerful nations and individuals to help address the root causes and drivers most commonly identified as being behind epidemics and pandemics outbreaks. Some of those drivers include (but are not limited to): poverty, inequity, violent conflict, inadequate public health provision, inadequate funding for prevention, the lack of an adequately integrated and well-funded ‘One Health’ global approach (WHO, 2017), environmental pressures and degradation, habitat destruction and human/host/reservoir interaction. Addressing the root causes and drivers behind epidemics is a monumental task but one which needs to be undertaken if we are to succeed in “coming together” (Brundtland, 2003) to prevent yet another global catastrophe.

Typhoid Mary 2.0 or all in the same storm

Alternatively, we are left with metaphors and narratives that externalise both the risk and the blame. For example, the poor (and ‘the other’) may be blamed for their ‘reckless’ behaviour – such as eating wild life, exploiting animals, or going back to unsanitary wet markets. This is akin to the blaming of the poor Irish immigrant to the US Mary Mallon some hundred years ago for her ‘persistence’ in working as a cook despite being an asymptomatic carrier of the highly contagious typhoid fever. To this day, instead of being a symbol of the refusal of the well-off to address the underlying conditions which made Mary Mallon (and others) forced to go back to the very same conditions that influenced the spread of the disease, she continues to be remembered as ‘Typhoid Mary’ – a killer of the affluent. Of course, if we are to prevent Typhoid Mary 2.0, 3.0, etc. we need to discard the fallacy of future personal exemption, as it makes many of us blind to the significance of minimising the previously mentioned drivers behind the spread of infectious diseases.

Being in the “same storm but not in the same boat” is the metaphor that probably best summarises the current situation. It is also important to point out the differential treatment different ‘boats’ (real and metaphorical) receive, depending on how close they are to wealth and power. Consequently, some were blind as to the possibility of luxury cruise ships being carriers of the dangerous diseases. This in turn led to numerous outbreaks of COVID-19, most notably in Japan and Australia: because how could Diamond Princess or Ruby Princess possibly be Typhoid Mary 2.0?

Present attention and fatalism: latest newsworthy issue and dodging the bullet

Yet more futures fallacies played a role in our collective lack of preparedness for COVID-19. The futures fallacy of present attention, for example, while helpful in futures issues framing, is also notable for its “narrow focus on the latest newsworthy issue” (AUTHOR, 2020a). Our cognitive biases influence us in a way that makes us tend to “assess the relative importance of issues by the ease with which they are retrieved from memory” (Kahneman, 2011: 8). And since “few of us have experienced a pandemic (such as COVID-19) … we [were]all guilty of ignoring information that doesn’t reflect our own experience of the world” (Horton, 2020a). Even when epidemics spread in some countries or regions of our common world, the rest of ‘us’ “kept on dodging a bullet [as]it was easy to attribute everyone else’s susceptibility to things that didn’t exist in our … way of life” (Henig, 2020, italics added). Those of us that “didn’t ride camels … eat monkeys [or]… handle live bats and civet cats in the marketplace” (Henig, 2020) – not being ‘complicit’, felt safe.

Such “biases of intuitive thinking” are apparent in “assigning probabilities to events, forecasting the future, assessing hypotheses, and estimating frequencies” (Kahneman, 2011: 8). As a consequence, pandemic preparedness and response in the public sector oscillate between cycles of ‘panic followed by neglect’ (WHO, 2017; Cameron et al., 2019; World Bank, 2017; UN, 2016). In other words, global panic during the latest potentially growing epidemic is usually followed by complacency and inaction when said epidemic subsides. Consequently, recommendations in relation to preparedness for future outbreaks are not implemented. As epidemic cycles wax and wane, due to the futures fallacy of present attention, over-reaction is followed by under-reaction, and much-needed consistency is found wanting. This, sadly, results in “a significant and preventable loss of life” (UN, 2016: 6).

The fallacy of present-attention is related to logical fallacies known as availability, attention or anchoring bias, which ignore or minimise phenomena that exist but cannot be remembered or retrieved with ease (AUTHOR, 2020a, 2020c). This may explain yet another finding by psychologists, as to why our ‘imaginations about the future’ are, by and large, ‘not particularly imaginative’ (Gilbert, 2007). We can see this in the frequency of risks framed in terms of the extrapolation of the present or recent situations. For example, the previously cited Global Risk Report by the World Economic Forum features pandemics as a major risk (amongst the top five) in 2007 and 2008 – in the aftermath of SARS 1 outbreaks – but not in the Global Risk Reports 2009-2019. 2013-2017 widespread Ebola outbreak is reflected in a number of “Futures Decks” during that period – decks used in workshops within the public policy sector. For example, here are concerns for the future, during the Ebola pandemic:

“Ebola mutates into a virus as contagious as the flu, creating a global pandemic.” (ForesighNZ, 2016)

“What if India is hit by Ebola? India has yet to be hit really hard by a global epidemic. India’s large population, inadequate health care and absence of a proper sanitation system would be hugely problematic in the face of something like Ebola.” (The Takshashila Future Deck, 2014)

And, in the aftermath of MERS, there were reports which:

“…focused on preparedness for a respiratory viral pandemic, with the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) given as the specific disease of concern”. (ECDC, 2015)

As I argued in the previous futures fallacies articles (AUTHOR, 2020a, 2020c), all of the fallacies have some benefits as well. Arguably, the countries praised for having both a good level of preparedness as well as acting early and decisively on the warning signs were the ones with a fairly recent and similar epidemic experience with SARS 1. Despite, or perhaps more accurately, due to their proximity to where COVID-19 first originated, Taiwan, Japan, Singapore and Vietnam were all praised for successfully limiting the spread of the virus early on in the crisis. While certainly not being the only factor, the ability to imagine the spread of the virus in the future – either based on past experiences or the understanding that it can happen to ‘us’ as well – seemed to have been helpful.

Fatalism: letting it run

Another helpful approach was to NOT succumb to the futures fallacy of fatalism. Fatalism in the context of pandemic preparedness refers to a “feeling that sudden disease outbreaks will emerge in capricious ways as ‘acts of God’”. (Morse, 1993: 10) Fatalism is one of the oldest – indeed, millennia-long – discourses in relation to pandemics. It co-existed with other alternative explanations in the past, and so to this day it co-exists with the alternative discourses which provide different explanatory narratives and subsequently request different measures. The table below summarises some key pre-20th C pandemic discourses.

Table 1. Pre 20th C Pandemics

| Examples |

Cause & death toll |

Explanatory narratives |

Measures |

| Antonine Plague, Plague of Justinian, Black Death/Bubonic Plague, Smallpox, Cocoliztli, Russian Flu, Cholera |

Viruses and bacteria

From 1million to 200 million |

Dominant:

The wrath of gods/evil spirits

Devil’s work

God’s punishment |

Appeasement of gods

‘Quaranta giorni’/40 days quarantine

Bleeding and purges

Early vaccination

Sanitation |

| Alternative:

“The Other” (foreigners, minorities)

The imbalance among ‘bodily fluids’ known as ‘humours’

Miasma – pollution theory |

All of those discourses continued to play a role in relation to the general lack of preparedness and adequate responsiveness in the COVID-19 pandemic. Humours and miasma transformed into ‘balance’ and ‘toxins’ discourse within contemporary alternative and complementary medicine (Shapiro, 2020). They joined forces with some equally powerful long-standing metaphors such as ‘natural selection’ and ‘the survival of the fittest’. During the COVID-19 pandemic, they transformed once again, this time into the narratives of ‘only those with pre-existing conditions’ and ‘herd immunity’. The –‘building up ‘natural immunity’ and ‘letting it run’ narratives are seen by some to be ‘the only realistic approach’ in managing COVID-19. Moreover, their proponents believe that “the price of natural selection … [remains]ethically acceptable.” (Lederberg, 1993: 4) Whatever the case may be, such narratives endure because they tap into our general “difficulty to accommodate to the reality that Nature is far from benign”, or, at the very least it “has no special sentiment for the welfare of the human versus other species.” (Lederberg, 1993: 3) Their endurance is also related to the horror we feel when imagining “the emergence of new infectious agents as threats to human existence”, including viewing pandemic as a “recurrent, natural phenomenon.” (Lederberg, 1993: 3)

Since looking at that reality of human existence is difficult, an alternative approach was taken during late 20th and early 21st centuries. ‘Natural’ and ‘supernatural’ explanations have formed an alliance which has been undermining governments’ and public health sectors’ epidemic/pandemic responses – previous, current and planned. Concretely, the natural/supernatural alliance is commonly behind anti-vaccine or vaccine hesitancy stances as well as anti-isolation/protection measures such as quarantines and the wearing of masks. Unfortunately, given their resilience throughout human history, we can assume that they will continue to influence the pandemic response (or the lack thereof) in the future. However, fortunately, many alternatives to these narratives also exist. A detailed exploration of these alternative discourses is beyond the scope of this paper, which aims to help us better understand the lack of pandemic preparedness and adequate response. What will suffice here is to briefly raise a couple of dilemmas which are explored in the final section of this paper.

From war to syndemics

The main measures currently in place to contain the COVID-19 pandemic – isolation, physical distancing, and hygiene/sanitation – are the direct result of the paradigmatic victory of ‘germ theory’. However, a number of researchers have raised questions regarding the usefulness of the ‘man vs microbe’ (Garrett, 1996) narrative as well as its connection to military/war narratives. While perhaps useful for previous and current levels of preparedness and response, these narratives are increasingly seen as problematic for the future, for various reasons.

To start with, viewing EID challenges – by researchers, policy makers and general public – as a “battlefield where the final outcome may be some form of victory in the continuing battle against disease”, has been problematised because such discourse “fails to take into account broader socio-economic dynamics or a holistic systems perspective”. (Black, 2015: 138-139, italics added) Over the last several decades, some researchers have thus argued for the abandonment of such approaches and metaphors. Many have also argued for the rethinking of solutions which predominantly arise from an anthropocentric worldview. Seeing ‘humans at the centre of an environment’ that contains microbes which should be eradicated so as to assure ‘infection-free’ human survival is, they argue, not only short-sighted, it is also “probably impossible” (Wilson, 1994). These researchers have argued for an alternative, eco-centric view instead, one which “envisions the human as one of many species eating, assisting and competing with each other in a world where many processes are cyclical or waxing and waning and evolving.” (Wilson, 1994, italics added) Like most other living organisms, microbes are ‘opportunistic’; they “thrive in the undercurrents of opportunity that arise through social and economic change, changes in human behaviour, and catastrophic events such as war and famine.” (Krause in Morse, 1993: xii, italics added) So instead of, or in addition to, waging full-fledged wars against them, perhaps a better approach would be to minimise those undercurrents of opportunities.

The narrative and metaphor that best expresses this alternative and emerging approach is probably the one of “syndemics” (Merrill, 2009). In a nutshell, the syndemics approach encourages focus “not just on disease interactions but on the fundamental importance of the social conditions that foster disease clustering and interfaces.” (Merrill, 2009: 16) The syndemics approach no longer construes an infections disease purely in terms of the notion of the “organism as a closed … self-contained, independent … unit and of the hostile causative agents invading it.” (Fleck cited in Merrill, 2009: 19) It has become fairly obvious by now that COVID-19, like most other infectious diseases, has disproportionally affected those with ‘underlying conditions’. Underlying conditions, or an array of non-communicable diseases, for their part, cluster “within social groups according to patterns of inequality deeply embedded in our societies.” (Horton, 2020b) The syndemic perspective, therefore: “… does not stop with the consideration of biological connections (myriad, complex, and fascinating as they may be), because in the human world disease develops within and is significantly influenced by the social contexts of diseases sufferers”. (Merrill, 2009: 21) Rather, this perspective provides a conceptual framework for “understanding diseases or health conditions that arise in populations and that are exacerbated by the social, economic, environmental, and political milieu in which a population is immersed.” (The Lancet, 2017: 881)

Perhaps COVID-19 will provide opportunities to move away from an anthropocentric worldview and the battlefield-based germ metaphors. Ideally, it may even help us address major issues such as “global warming, environmental degradation, global health disparities, human rights violations, structural violence, and wars [all of which]exacerbate syndemics with damaging impacts on global health.” (Hart and Horton, 2017: 888) This will require integration of multidisciplinary, including social science, research “into models of infectious disease emergence and evolution” (Morse et al, 2012: 1959) in order to better understand pandemics. And it will require the integration of data with narratives, metaphors as well as community input (Next Strain, 2020).

Conclusion

“Some may say that AIDS has made us ever vigilant for new viruses. I wish that were true. Others have said that we could do little better than to sit back and wait for the avalanche. I am afraid that this point of view is much closer to the reaction of public policy and the major health establishments of the world, even to this day, to the prospects of emergent disease.” (Lederberg, 1993, italics added)

Based on the investigation in this paper, we can assume that the public sector will continue to be impacted by futures fallacies well into the post-COVID era. To what degree this will be the case will depend on the type of narratives, including metaphors, we choose. To clarify two basic choices, the following table recaps the metaphors discussed in this article.

Table 2. Key Narratives and Metaphors

| Lack of Preparedness |

Improved Preparedness |

| Nobody knew |

It’s just a matter of time |

| Never before |

Pandemics as certain as death and taxes |

| Who would have thought? |

Time is running out; Use time wisely |

| Panic or neglect |

Ever vigilant |

| Sit back and wait for the avalanche |

If you fail to plan, you plan to fail |

| Let it run |

Infection-free utopia |

| Just the flu |

New disease, new approach |

| Acts of God |

Man vs microbe |

| Survival of the fittest |

Germ theory |

| Natural selection |

One Health: human, animal and environment |

| Herd immunity |

Awaiting vaccination |

| The next big one |

Act now |

| The boy who cried wolf |

Responding to the signals amidst the noise |

| Damned if you do and damned if you don’t |

Governments and citizens |

| Out of sight, out of mind |

All in this together |

| Dodging a bullet |

Battlefield |

| Not me and not ‘us’ |

All of ‘us’ are vulnerable |

| Nation as organism |

Emerging viruses know no country |

| Typhoid Mary |

Removing undercurrents of opportunity |

| Kung flu |

Same storm, different boats |

| China virus |

Coming together |

| Only those with pre-existing conditions |

Syndemics |

The table is based on narratives and metaphors that circulated prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Those on the left tend to decrease our agency, our ability to act. Those on the right tend to enhance our preparedness. The analysis is limited to publications in English and it would be of use to analyse narratives within different linguistic and cultural settings. More narratives and metaphors will certainly emerge as the pandemic evolves. Debates about the best use of (always limited) resources, as well as what are the most effective ways to address root causes of the specific emerging infectious diseases, will continue.

Finally, key recommendations already published in numerous government documents as well as in expert/scientific papers will be critical in how we collectively respond to the consequences of COVID-19 as well as how well we start preparing for the next pandemic. In this process, the choice of overarching narratives and key metaphors will be critical. Carefully chosen narratives and metaphors can enhance the ability to prepare for future pandemics. They can help ensure that we move toward a world where doing nothing moves to a syndemics-type approach. That is, we see ‘us’ – humans and nature – all in this together, as we co-evolve. Alternatively, unhelpful narratives and metaphors will continue to contribute to future realities in which most of us are ill-prepared or only a few of us are ready. In that scenario we continue to commit futures fallacies. Thus, the key question for the future is whether we can create and collectively choose stories that help us not only prevent EIDs but also create a better, more equitable and all-round healthier planet.

Acknowledgements

The research reported in this article was supported by the First Futures Research Grant, awarded by the Prince Mohammad Bin Fahd Center for Futuristic Studies (PMFCFS) and World Futures Studies Federation (WFSF). Its content is solely the responsibility of the author.

References

AHMPPI (2014) Australian Health Management Plan for Pandemic Influenza. Accessed 27 September from https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/ohp-ahmppi.htm

Baumgaertner, E. & Rainey, J. (2020) Trump Administration Ended Pandemic Early-warning Program to Detect Coronaviruses. Los Angeles Times. Accessed 12 October 2020 from https://www.latimes.com/science/story/2020-04-02/coronavirus-trump-pandemic-program-viruses-detection

Bin Larif, S. (2015) Metaphor and Causal Layered Analysis, in Inayatullah, S. & Milojević, I. (eds.) CLA 2.0: Transformative Research in Theory and Practice. Tamkang University: Tamsui.

Black, P. (2015) Causal Layered Analysis: Case study of Nipah virus emergence, in Inayatullah, S. & Milojević, I. (eds.) CLA 2.0: Transformative Research in Theory and Practice. Tamkang University: Tamsui.

Brownlie, J., Peckham, C., Waage, J., Woolhouse, M., Lyall, C., Meagher, L., Tait, J., Baylis, M. and Nicoll, A. (2006) Foresight. Infectious Diseases: Preparing for the Future. Future Threats. Office of Science and Innovation, London.

Brundtland, G.H. (2003) New Global Challenges: Health and Security from HIV to SARS. Geneva Centre for Security Policy, Geneva. Accessed 1 October, 2020, from https://www.who.int/dg/brundtland/speeches/2003/genevasecuritypolicy/en/

BFI (2017) Brunei Futures Deck. Brunei Futures Initiative. Centre for Strategic and Policy Studies: Brunei Darussalam.

Calof, J.L. & Smith, J.E. (2012) Foresight Impacts from Around the World. Editorial. Foresight 14(1): 5-14.

Cameron, H., Georghiou, L., Keenan, M., Miles, I., & Saritas, O. (2006) Evaluation of the United Kingdom Foresight Programme Final Report. PREST, Manchester Business School, University of Manchester: Manchester.

Cameron E., Nuzzo J., Bell J. (2019) Global Health Security Index: Building Collective Action and Accountability. Nuclear Threat Initiative and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Cheng, V.C.C., Lau, S.K.P., Woo, P.C.Y., and Yuen, K.Y. (2007) Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus as an Agent of Emerging and Reemerging Infection. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, Vol. 20(4), 660-694.

CISET (1994) Global Microbial Threats in the 1990s. Report of the NSTC Committee on International Science, Engineering, and Technology (CISET) Working Group on Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases. Accessed 10 October, 2020 from https://clintonwhitehouse3.archives.gov/WH/EOP/OSTP/CISET/html/toc.html

Coates, J. F. (2010) The Future of Foresight: A US perspective. Technological Forecasting & Social Change 77: 1428-1437.

Cohn, S.K. (2012) Pandemics: Waves of disease, wave of hate from the Plague of Athens to A.I.D.S. The Historical Journal, November 2012; 85(230): 535–555.

Conway, M. & Stewart, C. (2004) Creating and Sustaining Foresight in Australia: A Review of Government Foresight. Swinburne University of Technology, Australian Foresight Institute: Melbourne.

Cook, C.N., Inayatullah, S., Burgman, M.M., Sutherland, W.J., & Wintle, B.A. (2014) Strategic Foresight: How planning for the unpredictable can improve environmental decision-making. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, (2014): 1-11.

Cuhls, K. and Georghiou, L. (2004) Evaluating a Participative Foresight Process: ‘FUTUR – the German research dialogue. Research Evaluation, 13(3), 143-153.

Da Costa, O., Warnke, P., Scapolo, F., & Cagnin, C. (2008) The Impact of Foresight on Policy Making: Insights from the FORLEARN mutual learning process. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management 20(3): 369-387.

Dalglish, S. (2020) COVID-19 Gives the Lie to Global Health Expertise. The Lancet, 11 April 2020, Vol. 395(10231): 1189.

Dator, J. (2007) Governing the Futures: Dream or survival societies? Journal of Futures Studies, 11(4): 1-14.

Dator, J. (2011) Futures Studies and Futures Research, in W.S. Bainbridge (ed.) Leadership in Science and Technology. SAGE Reference Series on Leadership, SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA.

Davies, K. (2020) Blinking Red: 25 Missed Pandemic Warning Signs. GEN: Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News. Accessed 20 July, 2020 https://www.genengnews.com/a-lists/blinking-red-25-missed-pandemic-warning-signs/

Dorr, A. (2017). Common Errors in Reasoning about the Future: Three informal fallacies. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 116 (march 2017), 322–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.06.018

Department of Health and Ageing (2003) Returns on Investment in Public Health: An epidemiological and economic analysis. Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing, Australian Government: Barton, ACT.

Dreyer, I. & Stang, G. (2013) Foresight in Government: Practices and trends around the world. EUISS Yearbook of European Security. European Union, Institute for Security Studies, Paris.

ECDC (2015). Preparedness Planning for Respiratory Viruses in EU Member States: Three case studies on MERS preparedness in the EU. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC): Stockholm. Accessed 27 September from https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/media/en/publications/Publications/Preparedness%20planning%20against%20respiratory%20viruses%20-%20final.pdf

Garrett, L. (1996) Microbes Vs Mankind: The Coming Plague. Foreign Policy Association: New York.

GHSI (2020) The U.S. and COVID-19: Leading the World by GHS Index Score, not by Response. Global Health Security Index News, 27 April 2020, Accessed 12 October 2020 from https://www.ghsindex.org/news/the-us-and-covid-19-leading-the-world-by-ghs-index-score-not-by-response/

Gilbert, D. (2007). Stumbling on Happiness. New York: Vintage books. Random House.

Gilman, S.L. (1987) AIDS and Syphilis: The Iconography of Disease. MIT Press, October (43): 87-107. doi:10.2307/3397566

GPMB (2019) A World at Risk. Annual Report on Global Preparedness for Health Emergencies. Global Preparedness Monitoring Board: Geneva.

Greenblott, J.M., O’Farrell, T., Olson, R., & Buchard, B. (2018) Strategic Foresight in the Federal Government: A survey of methods, resources, and institutional arrangements. World Futures Review 11(3): 245-266.

Grey, S. & MacAskill, A. (2020) RPT-Special Report. Reuters, 8 April, 2020, Accessed 12 October 2020 from https://www.reuters.com/article/health-coronavirus-britain-path/rpt-special-report-johnson-listened-to-his-scientists-about-coronavirus-but-they-were-slow-to-sound-the-alarm-idUKL4N2BV54X

Guterres, A. (2020) COVID-19: UN Counters Pandemic-related Hate and Xenophobia. Accessed 12 September from https://www.un.org/en/coronavirus/covid-19-un-counters-pandemic-related-hate-and-xenophobia

ForesightNZ (2016) ForesightNZ Playing Cards. McGuinness Institute: Wellington.

Hart, L. & Horton, R. (2017) Syndemics: Committing to a healthier future. The Lancet, 04 March 2017, Vol. 389 (10072): 888-889.

Havas, A., Schartinger, D. & Weber, M. (2010) The Impact of Foresight on Innovation Policy-making: Recent experiences and future perspectives. Research Evaluation, 19(2): 91–104.

Henig, R.M. (2020) Why Weren’t We Ready for This Virus? National Geographic, June 2020. Accessed 20 July 2020 from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2020/07/why-werent-we-ready-for-this-virus/

Horton, R. (2020a) Coronavirus is the Greatest Global Science Policy Failure in a Generation. The Guardian. Accessed 24 July 2020 from https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/apr/09/deadly-virus-britain-failed-prepare-mers-sars-ebola-coronavirus

Horton, R. (2020b) COVID-19 Is Not a Pandemic. The Lancet, 26 September 2020, Vol 396: 874.

HSC (2005) National Strategy for Pandemic Influenza. Homeland Security Council: USA.

Ibrahim, H., Kamour, A.M., Harhara, T., Gaba, W.H., and Nair, S.C. (2020) Covid-19 Pandemic Research Opportunity: Is the Middle East & North Africa (MENA) Missing Out? Contemporary Clinical Trials September 2020 (96): 106106. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2020.106106.

Inayatullah, S. (2018) Foresight in Challenging Environments. Journal of Futures Studies, June 2018, 22(4): 15-24.

Jennings, L. (2017) Foresight in the Public Sector: 2017 update. AAI Foresight: Roadmaps to Strategic Foresight. http://www.aaiforesight.com/blog/foresight-public-sector-2017-update. Accessed 20 March 2020.

Jones, K.E., Patel, N.G., Levy, M.A., Storeygard, A., Balk, D., Gittleman, J.L., and Daszak, P. (2008) Global Trends in Emerging Infectious Diseases. Nature, 21 February 2008: 990-994.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, Fast and Slow. UK: Penguin books, Random House.

Kinsman, J., Angrén, J., Elgh, F. et al. (2018) Preparedness and Response Against Diseases with Epidemic Potential in The European Union: A Qualitative Case Study of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) and Poliomyelitis in Five Member States. BMC Health Services Research (18), 528.

Krause, R.M. (1993) Foreword, in Morse, S.S. (ed.) Emerging Viruses (xvii-xix), Oxford University Press: New York.

Kuosa, T. (2012) The Evolution of Strategic Foresight: Navigating Public Policy. Gower Publishing Limited: Farnham, Surrey.

Lederberg, J. (1993) Viruses and Humankind: Intracellular Symbiosis and Evolutionary Competition, in Morse, S.S. (ed.) Emerging Viruses (3-9), Oxford University Press: New York.

Merrill, S. (2009) Introduction to Syndemics: A critical systems approach to public and community health. Jossey-Bass: San Francisco.

Milojević, I. (2020a). Futures Fallacies: Our common delusions when thinking about the future. Journal of Futures Studies Perspectives. Accessed July 18, 2020, from https://jfsdigital.org/2020/07/18/future_fallacies/

Milojević, I. (2020b). Mirror, Mirror on the Wall, Who Should I Trust After All? Future in the Age of Conspiracy Thinking. UNESCO Futures of Education Ideas LAB. Accessed August 18, 2020, from https://en.unesco.org/futuresofeducation/milojević-mirror-mirror-wall-who-should-i-trust-after-all

Milojević, I. (2020c). Futures Fallacies. What They Are and What We Can Do About Them. Journal of Futures Studies. In Press. Accessed 12 October 2020 from https://jfsdigital.org/futures-fallacies-what-they-are-and-what-we-can-do-about-them/

Milojević, I. & Inayatullah, S. (2015). Narrative foresight. Futures, 73(October 2015), 151-162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2015.08.007

Morse, S.S., Mazet, J.A.K., Woolhouse, M., Parrish, C.R., Carroll, D., Karesh, W.B., Zambrana-Torrelio, C., Lipkin, W.I. and Daszak, P. (2012) Prediction and Prevention of the Next Pandemic Zoonosis. The Lancet, 2012(380): 1956–65.

Mosk, M. (2020) George W. Bush in 2005: ‘If we wait for a pandemic to appear, it will be too late to prepare’. ABC news, Accessed 29 September from https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/george-bush-2005-wait-pandemic-late-prepare/story?id=69979013

Morse, S.S. (1993) Examining the Origins of Emerging Viruses, in Morse, S.S. (ed.) Emerging Viruses (10-28), Oxford University Press: New York.

Murphy, F. (1998) Emerging Zoonoses. Emerging Infectious Diseases, Vol. 4 (3), 429-435.

Next Strain (2020) Real-time Tracking of Pathogen Evolution. Accessed 12 October 2020 from https://nextstrain.org

NIC (2000) The Global Infectious Disease Threat and Its Implications for the United States. National Intelligence Council. United States.

Ortu, G., Mounier-Jack, S. and Coker, R. (2008) Pandemic Influenza Preparedness in Africa Is a Profound Challenge for an Already Distressed Region: Analysis of National Preparedness Plans. Health Policy Plan, 22(3): 161-169.

Ross, A.G.P, Crowe, S.M., and Tyndall, M.W. (2015) Planning for the Next Global Pandemic. International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 38(2015): 89-94.

Rubin, H. (2011) Future Global Shocks: Pandemics. International Futures Programme and OECD.

Savio, N. & Nikolopoulos, K. (2009) Forecasting Effectiveness of Policy Implementation Strategies: Working with semi-experts. Foresight 11(6): 86-93.

Schartinger, D., Wilhelmer, D., Holste, D. and Kubeczko, K. (2012) Assessing Immediate Learning Impacts of Large Foresight Processes. Foresight 14(1): 41-55.

Shapiro, R. (2008) Suckers: How Alternative Medicine Makes Fools of Us All. Harvill Secker: London.

Silver, N. (2012) The Signal and the Noise: Why Most Predictions Fail – But Some Don’t. Penguin: New York.

Solem, K.R. (2011) Integrating Foresight into Government. Is it possible? Is it likely? Foresight 13(2): 18-30.

The Takshashila Future Deck (2014) Future Deck. The Takshashila Institution. Accessed 12 October 2017 from http://takshashila.org.in/the-takshashila-future-deck

Terranova, D. (2015) Causal Layered Analysis in Action: Case studies from an HR practitioner’s perspective, in Inayatullah, S. & Milojević, I. (eds.) CLA 2.0: Transformative Research in Theory and Practice. Tamkang University: Tamsui.

The Lancet (2017) Editorial. Syndemics: Health in context. The Lancet, 4 March 2017, Vol 389: 881.

UN (2016) Protecting Humanity from Future Health Crises: Report of the High-Level Panel on the Global Response to Health Crises. Accessed 11 October 2020 from https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/70/723

UNEP (2016) UNEP Frontier 2016 Report: Emerging Issues of Environmental Concern. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi.

UNDP (2014) Foresight: The manual. Global Centre for Public Service Excellence and UNDP: Singapore.

Van Asselt, M., Van Klooster, S., Van Notten, P. & Smits, L. (eds.) (2010) Foresight in Action: Developing policy-oriented scenarios. Earthscan: London.

Webster, R.G. (1997) Predictions for Future Human Influenza Pandemics. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, August 1997(176),14-19. https://doi.org/10.1086/514168

WHO (1999) Influenza Pandemic Plan. The Role of WHO and Guidelines for National and Regional Planning. WHO/CDS/CSR/EDC: Geneva

WHO (2009) Whole-of-Society Pandemic Readiness. Accessed 10 October 2020, from https://www.who.int/influenza/preparedness/pandemic/2009-0808_wos_pandemic_readiness_final.pdf?ua=1)

WHO (2015) Anticipating Emerging Infectious Disease Epidemics, WHO Informal Consultation Meeting Report. Geneva, Switzerland.

WHO (2017) Financing of International Collective Action for Epidemic and Pandemic Preparedness. The Lancet, 2017(5): 742-744.

WHO (2018) Memorandum of Understanding Between the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization and The World Organisation for Animal Health and The World Health Organization. Accessed 11 October 2020 from https://www.who.int/zoonoses/MoU-Tripartite-May-2018.pdf?ua=1

WHO (2019) WHO Launches New Global Influenza Strategy. Accessed 12 September 2020 from https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/11-03-2019-who-launches-new-global-influenza-strategy

WHO (2020a) Emergencies Preparedness, Response. Disease Outbreaks by Year. Accessed 10 October, 2020 from https://www.who.int/csr/don/archive/year/en/

WHO (2020b) Emergencies Preparedness, Response. Disease Outbreaks by Year. Accessed 10 October, 2020 from https://www.who.int/csr/don/archive/year/2020/en/

WHO (2020c) COVID-19 Pandemic. Numbers at a Glance. Accessed 01 October 2020 from https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019

Wilson, M. (1994) Disease in Evolution. New York Academy of Sciences: New York.

El Banco Mundial (2014) El presidente del Grupo del Banco Mundial pide un nuevo servicio de emergencia para una pandemia mundial . Consultado el 20 de septiembre de 2020 desde https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2014/10/10/world-bank-group-president-calls-new-global-pandemic-emergency-facility

Banco Mundial (2017) Del pánico y la negligencia a la inversión en seguridad sanitaria. Informe del Grupo de Trabajo Internacional sobre Preparación Financiera (IWG). Consultado el 12 de octubre de 2020 en http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/979591495652724770/pdf/115271-REVISED-FINAL-IWG-Report-3-5-18.pdf

El Banco Mundial (2018) Haciendo que la preparación para una pandemia sea financieramente sostenible en Asia oriental y el Pacífico . Consultado el 21 de septiembre de 2020 desde

https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2018/02/28/making-pandemic-preparedness-financially-sustainable-in-east-asia-and-the-pacific

Foro Económico Mundial (WEF) (2007-2020) Riesgos globales . Foro Económico Mundial, Ginebra